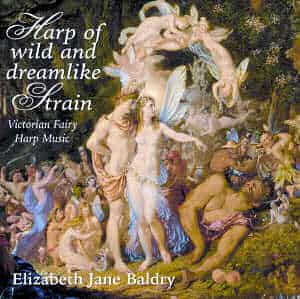

Victorian Fairy Harp Music

Premiere Recordings of 19th Century Harp Music

“Harp of wild and dreamlike strain,

When I touch thy strings,

Why dost thou repeat again

Long-forgotten things?”

Emily Brontë

The Beauty of a Vanished World

I fell in love with all things Victorian as an adolescent. Being also wildly in love with my harp, I read descriptions of Victorian harp music as “an ideal music…surging waves of melody and rhythm”. This inspired me to seek out the forgotten music and share it with today’s audiences.

So one sunny Spring day in the 1990s, I walked nervously up the steps to the British Library. This was in the days of the Old Round Reading Room. It felt wonderful to be in that incredible space – I could almost hear the swish of George Elliot’s skirts and the whisperings of Dickens. The sheer quantity of old harp music in the archives took my breath away. For two years, I immersed myself in the evocative world of Victorian fairies selecting music to memorise and record.

And then a stroke of luck! An opportunity arose to record the CD in the Victorian domed ballroom of a vast rambling Devon mansion on a hidden estate in mid Devon. The house had over a hundred empty rooms and was inhabited only by a caretaker, his wife, and two delightful, if somewhat feral, children. The interior halls were bathed in eerie otherworldly light thanks to green tarpaulins stretched over leaking glass cupolas high up in the roof!

Something of the magic of that – allegedly haunted – ballroom has been captured in the recording. There’s been no digital meddling. The ethereal acoustic is entirely natural. Listen carefully, and you might even hear the birds singing outside in the overgrown garden.

Listen to a free track now

Fairies and Harps in Victorian England

This article was first published in ‘Enchanted Living’ (formerly Faerie Magazine),

one of America’s leading lifestyle magazines.

During the nineteenth century a musical genre arose in England that beautifully captured the spirit of the age. This charming art form flowed from many aspects of nineteenth century society – the decline of religion, the first wave of feminism, the rise of Spiritualism and Theosophy, anthropology, antiquarianism, the reaction against Darwinism, the relentless advance of the middle classes, the repression of sexuality, the nostalgia for a rapidly vanishing rural past and the awakening of interest in our folklore heritage. All these fascinating topics combined to produce Victorian Fairy Harp Music, the quintessence of Victorian romanticism and one of its best-kept secrets.

The subject of fairies in Victorian culture is a vast, teeming ocean of spellbinding delights that could fill several volumes. The harp – long associated with the Otherworld – was perfectly placed to absorb this potent Victorian passion.

“The harp it hath a magic power,

For fairies hover o’er each string”

Thomas Aptommas, 1859

Sexual Repression in Victorian England

The Victorian Age was a period of cataclysmic social change and monstrous hypocrisy. The unhealthy preoccupation with respectability and conformity forced the natural desires and impulses of men and women underground.

Behind a facade of moral uprightness, the typical middle class Christian gentleman ran a business in which the workers – including women and young children – were sickeningly dehumanized, seen as mere sources of energy of no more value than coal. His virginal wife was bred to be a decorative rather than a useful member of society. She was often infected with his syphilis on her wedding night. He visited brothels or kept a mistress: one in every sixty houses in London was a brothel compared to one in six hundred today. In his library, books by male and female authors were kept on separate shelves – unless their respective authors happened to be married! Even chair and piano legs in his house were frequently draped so as not to incite passions. The very word “leg” was rarely spoken in polite society.

He required his wife to be the purest angel of his home: childlike, an idealised mother, submissive to him, always charming, selfless and self-sacrificing. A lively intelligence was not to be borne. Upon marriage, all of her money and any property belonging to his new wife automatically became his.

Forbidden Fruits

Such hypocrisy and double standards created a dark underbelly in Victorian society which found its outlet in an absolute obsession with fairies.

During the nineteenth century, more and more women began to question the status quo. “The bible and the church have been the greatest stumbling blocks in the way of women’s emancipation” declared the Victorian Free Thought Magazine. Our tightly corseted great great grandmothers must have gazed with yearning on those fashionable Victorian fairy paintings. Fairies and their Queen were non-monogamous and non-maternal. They loved music, dancing, and sex. They wore diaphanous, loose and flowing robes instead of whalebone corsets. They ran free and wild, indulging in orgiastic revels and delicious debauchery. In short, fairies embodied everything that was forbidden to Victorian women.

Adult fairy tales featuring fairy femme fatales proliferated, expressing male anxieties about female power and fantasies of destructive female sexuality. George MacDonald’s Lilith, for example, portrays a fairy vampire who seduces and sucks the blood of men. St. Bride of the Mantle in Fiona Mcleod’s “By the Yellow Moonrock” kisses the hero Rory and sucks his soul out through his lips, leaving them blue and swollen, a drop of black blood in the throat of his stiffening corpse.

“Victorian Fairies were certainly not the

“painty-winged, wand-waving, sugar-and-shake-your-head

set of imposters”

Rudyard Kipling

Fairies and Anthropology

The new science of Anthropology brought another startling dimension into the melting pot. Pygmies were discovered in Africa and exhibited in zoos, sometimes even with bones strewn in their cages to startle the visitors with images of cannibalism. Women fainted from the shock of seeing them.

The Scottish folklorist David MacRitchie put forward a theory that fairies were the remnants of a race of non-Aryan people, a race older than homo sapiens. Such a race existed alongside normal men until at least the eleventh century, building houses underground and thus giving rise to the traditional fairy mounds. In 1893, Neolithic pygmy skeletons were found buried with full-size Europeans on an archeological dig in Switzerland. Speculation abounded that perhaps this race of little people was still extant, lingering on in forests and hidden places, stealing babies and young women to boost their diminishing stock.

The fear of one’s baby being stolen by the fairies was hideously real and terrible in the nineteenth century. The Daily Telegraph of May 17th 1884 carries the story of two women arrested for placing a baby on a hot shovel. They were convinced the infant was a changeling because it did not have the use of its limbs.

The Irish Wife Murdered for Being a Fairy

It is important to recognise the absolute belief most people had in fairies in order to understand the fascination of the general public for the subject. A further chilling example will dismiss the common misconception of fairies as nursery nonsense: the sensational murder of Bridget Cleary in Ireland in 1895 which made headlines around the world. Bridget Cleary was a spirited young woman of twenty-six married to a cooper, Michael. They lived with her father in a new labourer’s cottage that had been built on the site of a fairy fort. Her husband became convinced that

Bridget had been abducted by the fairies and a changeling left in her place. He consulted the local “fairy doctor” who advised the necessary treatment to restore the real Bridget.

On the first night of the cure, Bridget was held down by her cousins and force fed milk mixed with a herbal decoction whilst being anointed with water, urine and hen’s excrement. She was then held over the fire to drive the fairy out of her.

The following night, several family members and friends subjected the poor girl to further interrogation and abuse. Michael poured lamp oil over her and set her alight. As she writhed in agony, he reassured the onlookers that she would soon fly up the chimney. He then went and maintained a pitiful vigil at the fairy hill for his real wife to be returned to him. He waited three nights. Bridget did not come. The gruesome, charred body of the supposed changeling was subsequently found buried. Nine people were arrested.

Other Ideas about the Nature of Fairies

The Folklore Society was founded in 1878 to study the rich heritage of British folk and fairy mythology. Scientific methods were very much in vogue and folklorists started collecting tales in earnest. The Theosophists and Spiritualists rejected the pygmy theories and put forward ideas of nature spirits, relics of goddess worship or the spirits of the dead.

Why the Harp expresses the Spirit of the Age

The harp’s associations with the Otherworld go back to antiquity. In Mesopotamia, royal harpists were buried alive in the tomb of their monarch when he died. Ancient Egyptian tomb paintings reveal the harp as central to Egyptian culture. Anglo-Saxon chieftains were buried with a harp at their feet to act as a bridge to the afterlife.

The harp in the nineteenth century had finally developed into its current form having fallen out of favour during the previous century on account of its technological limitations. Every respectable drawing room contained a harp. It was the young lady’s instrument par excellence, displaying dainty wrists and forearms to their best advantage. Activating the seven pedals around the base of the instrument gave the player a tempting opportunity to flash her ankles. Her sexuality was her most potent weapon and players cannot have been unaware that the harp is seductive to both eye and ear with its flowing harmonic curve and gilded angels. William Makepeace Thackeray asks what causes girls “to play the harp if they have handsome arms and neat elbows…but that they will bring down some desirable young man with those killing bows and arrows of theirs.” Another example of male fears of predatory, dangerous females!

Fashionable Fairy Harp Music

Composers of the nineteenth century wrote harp music on fairy subjects to satisfy the demand of the new middle classes. These are works of great technical brilliance with luscious sweeping arpeggios and bewitching melodies. Evocative titles create an aura of romance – The Dance of the Spirits, Recollections of the Enchantress, A Fairy Legend. The composers themselves gave performances of the music which thrilled audiences, tapping into the forbidden fruits of the Victorian fairy obsession. Our great, great grandmothers must have listened with smouldering passion, sweating into their corsets as they surrendered to the spell of fairy harp music. Think of them listening, imagining the bliss of bare feet in moist, dewy grass; dancing with joyous freedom in glittering fairy halls; gorging on pungent fairy fruits with lethal, thrilling, earthy lusts coursing through their veins. Think of them when the music ended as they left the luscious, enchanted world behind them and returned to their limited lives as submissive, self-sacrificing wives and mothers.

The Demise of the Victorian Fairies

Times changed. Fairies moved into the nursery where they were trivialised, their erotic and occult aspects expurgated. The appetite for the esoteric faded with the harsh realities of the Great War. Victorian Fairy Harp Music went out of fashion and languished in dusty archives. Twentieth century harpists denounced it.

“They sat entranced as if in some blest dream

They heard the witching melody of heaven;

For at that harpist’s touch such notes were given –

So sweet and strange, they more than mortal seemed.”

But now, like Sleeping Beauty, the music has been awakened from its long sleep, and can be heard again. Victorian Fairy Harp Music is a vivid doorway into a bygone age. This little sub-genre of British musical history is so charming in its nostalgic sentiment, and yet carries within its mystical heart the entire story of the Victorian esoteric world.

Harp of Wild and Dreamlike Strain

Elizabeth-Jane spent two years researching and studying Victorian Fairy Harp Music discovered in the archives of the British Library. The resulting album, Harp of Wild and Dreamlike Strain, is the first opportunity to hear this enchanting music in modern times.

Click here to buy the CD or download the Album